More Information

Submitted: March 30, 2021 | Approved: April 07, 2021 | Published: April 08, 2021

How to cite this article: Parro-Pires DB, de C Matias Barros SH, Araújo FSHD, Santos DZ, Nogueira-Martins LA, et al. Burden and depressive symptoms in health care residents at COVID-19: A preliminary report. Insights Depress Anxiety. 2021; 5: 005-008.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ida.1001024

Copyright License: © 2021 Parro-Pires DB, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Burden and depressive symptoms in health care residents at COVID-19: A preliminary report

Daniela Betinassi Parro-Pires1* , Sérgio Henrique de C Matias Barros2, Fernanda Sabina HD Araújo3, Daniel Zandoná Santos2, Luiz Antônio Nogueira-Martins4 and Vanessa de Albuquerque Citero5

, Sérgio Henrique de C Matias Barros2, Fernanda Sabina HD Araújo3, Daniel Zandoná Santos2, Luiz Antônio Nogueira-Martins4 and Vanessa de Albuquerque Citero5

1MSc, Psychologist, NAPREME, Department of Psychiatry, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil

2MD, Psychiatrist, Department of Psychiatry, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil

3Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil

4MD, PhD. Former Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil

5MD, PhD. Affiliated Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil

*Address for Correspondence: Daniela Betinassi Parro-Pires, MSc. Psychologist, NAPREME, Department of Psychiatry, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil, Tel: 55 11 992788271; Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

This paper focuses on the mental health burden on medical and healthcare residents during the 1st wave of COVID-19 pandemic crisis in 2020 describing the activities of a mental health service for residents (NAPREME) in a public university, UNIFESP, Sao Paulo, Brazil; and a preliminary study showing an increasing of depressive symptoms and depression among residents. Data is related to the screening interviews of medical residents and healthcare multi-professional residents who sought the mental health service from March to December 2020. A comparison was conducted with the same period in 2019 (covering a period when Covid-19 was not affecting the Brazilian population). There was a 22% demand increase in 2020. Of the total amount who sought treatment: 23% were medical residents, 22% nursing residents, and the remaining distributed among other professions; and 58% were first year residents and 34% second year. Data from the BDI questionnaire showed some variance between the two years: the mean score for 2020 was 24.67 (± 7.86) which is in the depression range, higher than the mean score of 19.91 points in the previous year (± 10.15) which is only in the depressive symptoms range (p < 0.005). In the pandemic period there was an increase in residents with depression from 49% to 70%. Depression, anxiety, stress and burnout syndrome were observed, demanding psychological and psychiatric care for this population. Assessment of residents’ mental health will continue during 2021, during the 2nd wave of COVID-19 and an additional analysis will be conducted along the year.

The World Health Organization declared the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) as a public health emergency in January 2020 [1-3] and in Brazil the outbreak started in March 2020.

In a pandemic outbreak, as in COVID-19, it is essential to consider the emotional burden, besides physical aspects of the infectious disease. Anxiety, depression and stress, present in the general population, were particularly significant for health care workers in different countries and continents [1-8].

This paper focuses on the mental health burden on medical and healthcare residents during the 2020 first wave COVID-19 pandemic which involved the risk of being infected (as none had been vaccinated during this period) and the exposure to stressful situations. It describes the activities of a mental health service for residents in a public university, UNIFESP, Federal University of Sao Paulo, in Sao Paulo, Brazil. This service, named NAPREME (Residency assistance & research center), started its activities in 1996 and assists medical residents and healthcare multi-professional residents - including nurse, physiotherapist, dentist, nutritionist, speech therapist, social worker, psychologist, occupational therapist and others. NAPREME offers psychological therapy and psychiatric consultation for these residents focusing mainly on work related crisis. These residents work at Hospital Sao Paulo (HSP), associated with UNIFESP.

The manuscript describes a preliminary study in Brazil showing an increasing of depressive symptoms and depression among residents during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. The data described in this paper is about the initial interview conducted when residents searched for the service between March and December 2020. In this period, Brazil presented the first wave of COVID-19, from March to July, but sustained a high plateau of cases till December. The Hospital Sao Paulo was converted to a mixed COVID and non-COVID hospital with 30% of beds to COVID patients.

A comparison was conducted with the previous year’s data, 2019, covering a period when Covid-19 was not affecting the Brazilian population.

All initial interviews - screening interviews - were conducted online by a psychologist and lasted about 1 hour (previously COVID-19, all interviews and consultations were in person). After the interview, a psychological and/or psychiatric treatment were suggested, and, if necessary, another referral for medical evaluation. Residents could spontaneously require the interview or could have been referred by a teacher, a doctor or even a friend.

The interview comprises data about gender, age, marital status, place of birth, habitation, whether the resident had a previous mental health treatment, and personal/family psychiatric history and residency program. The Brazilian version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [9] was also answered and the interview included the reason for seeking treatment. The BDI assesses the existence and severity of depression symptoms, ranging from 0 to 63 points, considering as having depressive symptoms anyone who reaches a score higher than 15, and depression higher than 20 according to the Brazilian validation.

There were 78 screening interviews from March to December, 78% of them occurred from spontaneous demand. Compared to 2019 (no COVID), there was an increase of 22% of screening interviews, with a similar percentage regarding the spontaneous demand.

Since the beginning of NAPREME service, the peak of screening interviews usually comes about at the sixth, seventh or eighth month after the beginning of the residency. During 2020, the similar percentage of total interviews (around 25%) occurred in these months, however, additionally to this peak, another peak was observed in the second and the third months after the residency onset, 26%.

From all residents who were interviewed during these months, 23% were medical residents, 22% nursing residents, being the remaining distributed among other professions. 58% were first year residents and 34% second year.

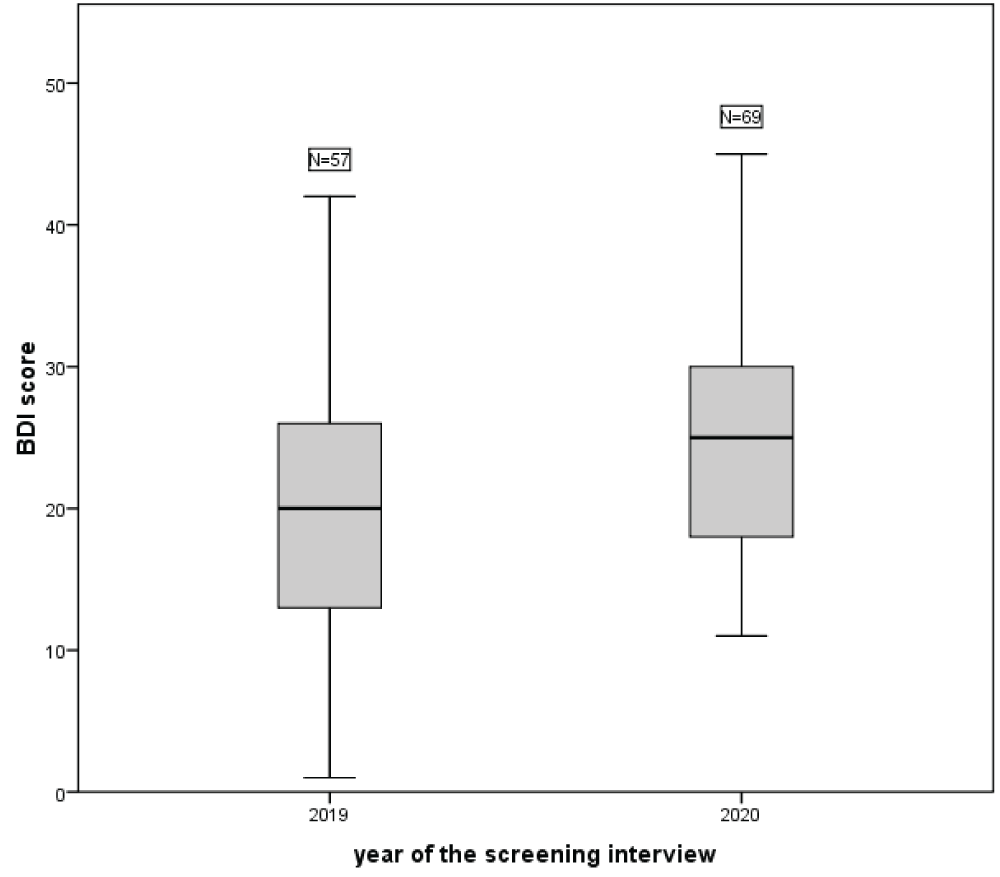

Data from the BDI questionnaire also showed some variance between the two periods under analysis. Graph 1 shows that the mean score for 2020 was 24.67 (± 7.86, range from 11 to 45), which is in the depression range, higher than the mean score of 19.91 points in the previous year (± 10.15, range from 1 to 46), which is in the depressive symptoms range (t = -2.963; d.f. = 124; p = .004; CI 95% from -7.930 to -1.579).

Figure 1: Health professional residents’ mean score of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) from March to December of 2019 (pre-pandemic) and 2020 (during the 1st wave of pandemic).

Considering the cut-off point validated for the Brazilian population, the percentage by level of depression for the periods under analysis is the following (Table 1).

| Table 1: Health professional residents’ classification of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) from March to December of 2019 (pre-pandemic) and 2020 (during the 1st wave of pandemic). |

||

| 2019 | 2020 | |

| No symptoms | 39% | 14% |

| Depressive symptoms | 12% | 16% |

| Depression | 49% | 70% |

The deterioration of the mental health of residents due to the COVID-19 pandemic is evident – of all residents who sought treatment there was an increase in those classified as with depression from 49% to 70%.

Another indicative of the worsening of mental health of residents – specifically of medical residents – can be assessed by comparing the total amount of first year medical residents during the COVID-19 crisis and data from a study in which all UNIFESP’s first year residents answered BDI 8 months after the beginning of the program [10]. While in the latter there was no resident classified with Depression, NAPREME’s COVID-19 data shows 4 first year medical residents with Depression.

Previous to the COVID period, it was very usual that residents presented, in the first six months, adjustment disorders as an acute stress reaction caused by the life changes involved in initiating a residency program (changes in city, university, residency rounds), then anxiety and depressive disorders appeared along the year. Complaints and difficulties were related to the relationship inside the university and the hospital environment, dealing with patients, families, patient’s death, also appear as relevant.

After coronavirus disease, the demand for psychological and psychiatric care had some changes. From March to July, it was related to the forced isolation from their own families, to the fear of becoming infected with COVID, and transmitting it to their loved ones. As the residency had just started, adding the need of social distance and all restrictive measures, anxiety, depression, loneliness, avoidance behavior, anger could be observed. On one hand the work increased, on the other hand positive experiences decreased. Some strategies were not coping with the usual problems. There was an increased number of deaths, and some residents felt identified with the family of the deceased, who could not say goodbye to their loved ones. Practicing sports or going out to relax were no longer options. Most residents mentioned that they were eating more or drinking more alcohol when they were at home. Some developed compulsive behavior as cleaning hands inside their own house.

During this period, a great number of residents were infected with COVID. Each absence overloaded their team, but also gave hope that survival was a real option. For those residents who lost some family members or a teammate, it was difficult to return to their job. However, being at home alone was felt not as a good option.

From August onwards, the fear decreased and fatigue prevailed. Even with depressive and anxiety demands, during screening interviews it was observed burnout syndrome as they mentioned the severity of their work.

In 2020 NAPREME kept attending residents who were enrolled in the service in the previous year and added 2020 entrants. Of the total amount of patients in the service, during this period, there was an increased need for psychiatric support - only five patients were not medicated.

General Interventions:

In order to avoid more psychological damage some issues could be addressed to help residents cope with this new situation:

• Learning to make lists and prioritize realistic tasks, which may help to decrease the anxiety.

• Learning the variability of responses which in-patients could present, it may allow them to be better prepared for their reactions. Some residents felt intense guilt for doing or not doing an action, or for saying something which they were not responsible for. During COVID pandemic, they were forced to learn about not having control.

• Not feeling shame about their feelings. To recognize the difference between feeling hate or tired with a patient (and recognize it) and really do something harmful to them.

• Seeking supervision or peer consultation, even though most of the staff and residents face lack of time.

• Learning to encourage peer support as a strategy to cope with daily tasks and workload and share experiences. On the order hand, not having workload management, it may erode the group stability.

• Finding time to “reset” and consider realistic expectations; many times it would not be possible to avoid frustrations and uncontrollable events.

• Outside their work environment, even when isolated, it is important to try to maintain social contacts (even on line), maintain basic bodily care.

• And drop-in sessions with the mental health team is always an option.

The assessment of UNIFESP residents’ mental health will continue during 2021 – being with a better pandemic scenario in which vaccination improves overall situation or with a worse scenario in which different mutations of the virus have a more severe impact on patients. Additional analysis will be conducted along the year.

Ethical considerations

The reported data are the result of the service’s routine assistance record; dispensing with the consent form for the publication of the data.

- Wong AH, Pacella-LaBarbara ML, Ray JM, Ranney ML, Chang BP. Healing the Healer: Protecting Emergency Health Care Workers' Mental Health During COVID-19. Ann Emerg Med. 2020; 76: 379-384. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32534830/

- Talevi D, Socci V, Carai M, Carnaghi G, Faleri S, et al. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr. 2020; 55: 137-144. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32489190/

- Wang S, Wen X, Dong Y, Liu B, Cui M. Psychological Influence of Coronovirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on the General Public, Medical Workers, and Patients With Mental Disorders and its Countermeasures. Psychosomatics. 2020; 61: 616-624. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32739051/

- Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Di Lorenzo G, Di Marco A, et al. Mental Health Outcomes Among Frontline and Second-Line Health Care Workers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3: e2010185. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32463467/

- Walton M, Murray E, Christian MD. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020; 9: 241-247. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32342698/

- Spoorthy MS, Pratapa SK, Mahant S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic-A review. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020; 51: 102119. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32339895/

- Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety Among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020; 323 :2133-2134. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32259193/

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3: e203976. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7090843/

- Gorenstein C, Andrade L. Validation of a Portuguese version of the Beck Depression Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in Brazilian subjects. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1996; 29: 453-457. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8736107/

- Parro-Pires DB, Nogueira-Martins LA, Citero VA. Interns' depressive symptoms evolution and training aspects: a prospective cohort study. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2018; 64: 806-813. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30673001/